The Symbolism of Death & Rebirth in Yogic Philosophy

In every spiritual tradition, few symbols are as universal, or as misunderstood, as death and rebirth. In yoga, these ideas are not limited to the literal end of life, nor are they confined to mystical metaphor. Instead, they describe a continuous process of dissolution and renewal woven through the fabric of existence itself.

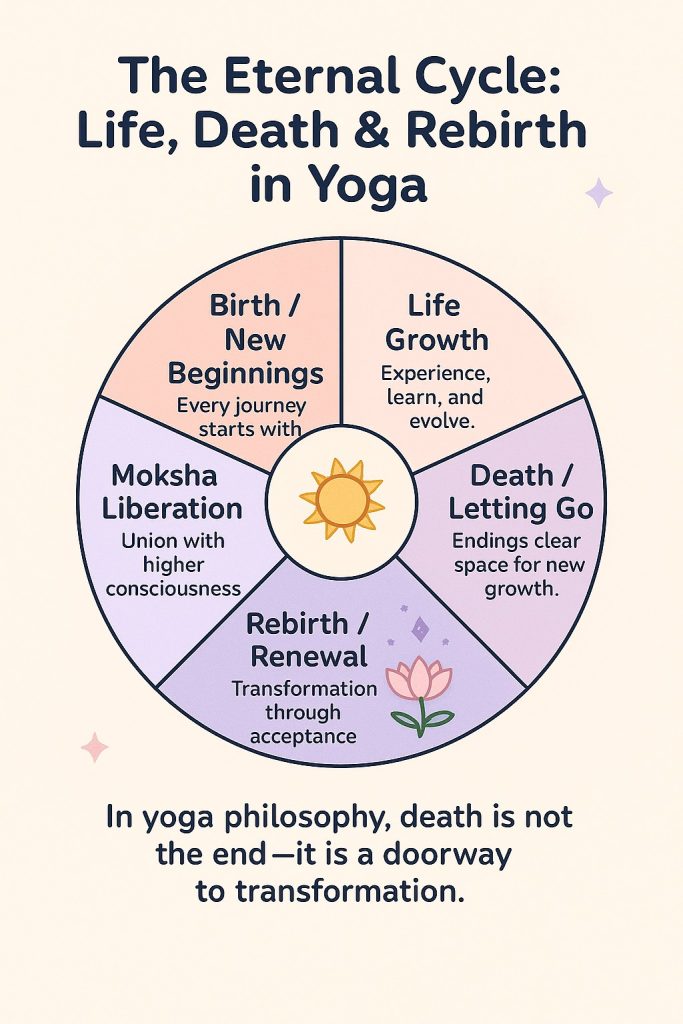

Yogic philosophy teaches that everything in the cosmos is engaged in an endless cycle of emergence, transformation, and return. Within this framework, the individual practitioner is invited to confront not only the inevitability of physical death but also the subtler “deaths” of ego, identity, and illusion that mark the path toward awakening. It is only with this broader horizon in view that the traditional teachings on saṃsāra, karma, and liberation begin to reveal their full meaning.

Yogic traditions regard life and death as two phases of a continuous cosmic process. The cycle of saṃsāra (birth, death, rebirth) is driven by karma (action and its consequences), from which the practitioner seeks liberation (mokṣa). Across Vedanta, Sāṃkhya, and Yogic schools, the ātman or puruṣha (Self) is eternal and untouched by bodily death. For example, the Bhagavad Gītā declares: “The soul is neither born nor does it ever die… It is eternal, immortal… not destroyed when the body is destroyed”. Likewise, the Upaniṣads exhort the seeker to move “from death to immortality”, emphasizing that liberation lies beyond the cycle of birth and death.

Vedanta and the Upanishadic View of the Self

Vedanta, drawing on the Upaniṣads, teaches that the ātman (Atman) is identical with Brahman and transcends physical death. The Upaniṣads repeatedly affirm the Self’s deathlessness: one mantra says

“From the unreal lead me to the real… from death lead me to immortality”. In Katha Upaniṣad, Death himself instructs Naciketas: “The intelligent self is neither born nor does it die… It is birthless, eternal, undecaying, and ancient. It is not injured even when the body is killed ”

This reflects the core Vedantic symbol: the individual soul is a part of the one eternal reality, merely veiled by ignorance. Metaphors abound: life is likened to an upside‐down sacred fig tree (aśvattha) rooted in the eternal Brahman, and the process of rebirth is as natural as changing garments “Just as a person casts off worn-out garments and puts on new ones, so the embodied Self casts off its worn-out bodies and enters others that are new”.

Vedanta thus treats death symbolically as a transition of the immutable Self into a new form, not as an end. “What we think of as ‘me’ is an imagined persona… as a result, there is no one to die,” notes one commentator, reflecting the Upaniṣadic insight that the ego is a temporary construct. Ultimate liberation (mokṣa) occurs when the illusion of individuality is “sacrificed” and one realizes the timeless Self. This state of jīvanmukti (liberation in life) is sometimes described in Vedanta as existing beyond birth and death altogether.

Bhagavad Gītā: Duty, Death, and the Immortal Soul

The Bhagavad Gītā (7th–8th century CE) synthesizes Vedantic and Karmic themes. It repeatedly stresses that the soul is eternal and unaffected by physical death. Arjuna’s grief in battle is met by Krishna’s teaching that killing the body is not killing the soul. The Gītā even uses the garment metaphor above to convey reincarnation. In Chapter 2 Krishna proclaims that the wise grieve neither for the living nor the dead, for the soul transcends death. Thus in the Gītā, death is a change of state, not annihilation.

Metaphorically, the Gītā and other Pāṇḍava texts see karma as the mechanism driving rebirth: actions leave impressions (saṃskāras) that “clothe” the eternal Self in successive bodies. Psychologically, Arjuna’s despair symbolizes attachment to a limited self; Krishna’s counsel is to transcend that limited ego and see the Self as immortal.

In practical yoga terms, the Gītā teaches acting in the world without ego-identification (karma-yoga), thereby slowly “dying” to selfish desires while living, which purifies the mind and leads toward liberation. This aligns with Vedanta’s emphasis on jñāna (knowledge) freeing one from the “jaws of death”.

Sāṃkhya and Classical Yoga (Patañjali): Purusha, Prakṛti, and Liberation

Sāṃkhya philosophy (often paired with Yoga) posits two realities: puruṣha (consciousness) and prakṛti (nature). In Sāṃkhya both souls (puruṣhas) and matter (prakṛti) are eternal. Liberation consists in the puruṣha realizing its separation from prakṛti.

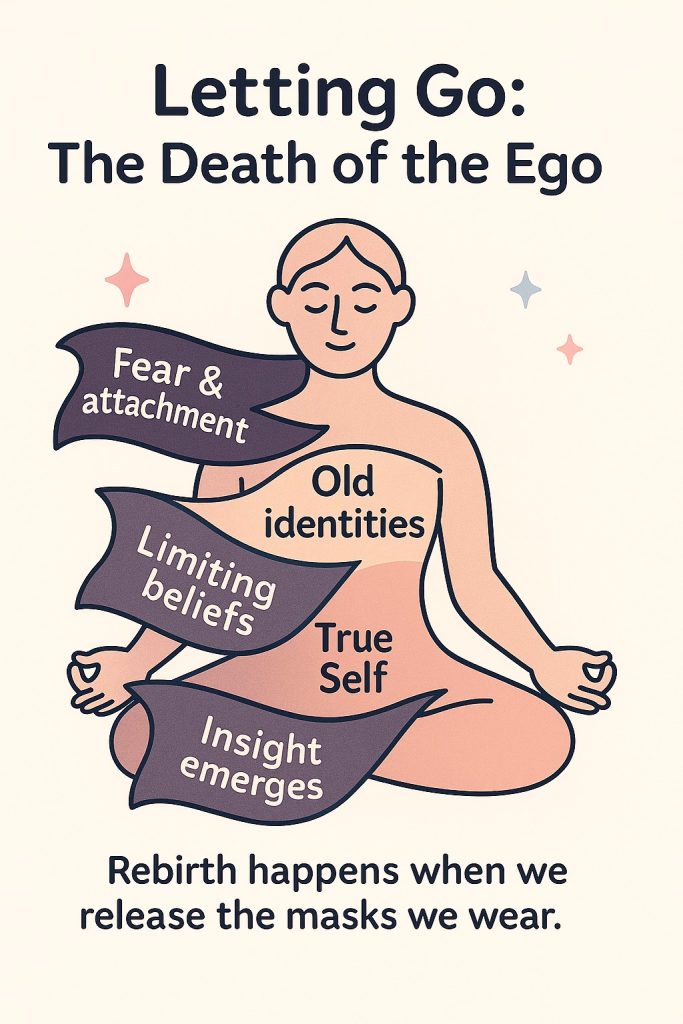

Both Sāṃkhya and Patañjali’s Yoga assert that the true Self is “pure, eternal, [and] free” it “can be neither born nor destroyed”. The apparent bondage of the soul to the body is an illusion (avidyā) caused by identifying with the mind-body (the ego asmita). When that illusion dissolves (through yoga or knowledge), the ego or “little self” is metaphorically killed: “the human personality… is destroyed—that is, it ceases to act—as soon as revelation becomes an accomplished fact”. In other words, the ‘death’ of the ego-self accompanies the awakening of the true Self.

Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtras (around first millennium CE) outline an eight-fold path (ashtanga) culminating in kaivalya (isolation) or “oneness”. Classical yoga speaks of attaining a state where the yogi is “motionless like a stone…He neither hears nor smells…he notices no touch…[and] does not desire anything”. This state – akin to living liberation (jīvanmukti) – is often described as a little death that occurs while living: the practitioner “dies” to all worldly fluctuations.

Eliade summarizes: “the yogi endeavors totally to ‘reverse’ normal behavior… on all levels of human experience he does the opposite of what life calls on him to do… The ‘reversal’ of normal behavior places the yogi outside life”. This anticipatory “death” is immediately followed by a symbolic rebirth into a transcendent mode of being. Liberation is thus metaphorically a kind of death-and-resurrection: the yogi “dies” to the profane self and is reborn into the true, changeless Self.

Sāṃkhya-Yoga also offers a metaphysical explanation for rebirth. The tattvas (fundamental principles) of nature are thought to regress back into prakṛti at death, which Eliade notes “signifies an anticipation of death”. Yogic and Tantric visualization practices sometimes mimic this elemental breakdown as if “anticipated visualization of the decomposition of the elements and their return into the circuit of nature, a phenomenon normally initiated by death”. Thus even the microcosm of yoga practice ritually enacts the macrocosmic reality of death and renewal.

Tantric Perspectives: Deities, Ritual Death, and Rebirth

Tantra – especially the Śākta (goddess) tradition – embraces death imagery as sacred. Goddesses like Kālī symbolize the cycle of destruction and regeneration. Kali’s iconography “embodies the grim realities of blood, death and destruction”, yet she is also understood as the mother who “bestows liberation (moksha)” and identifies with ultimate reality.

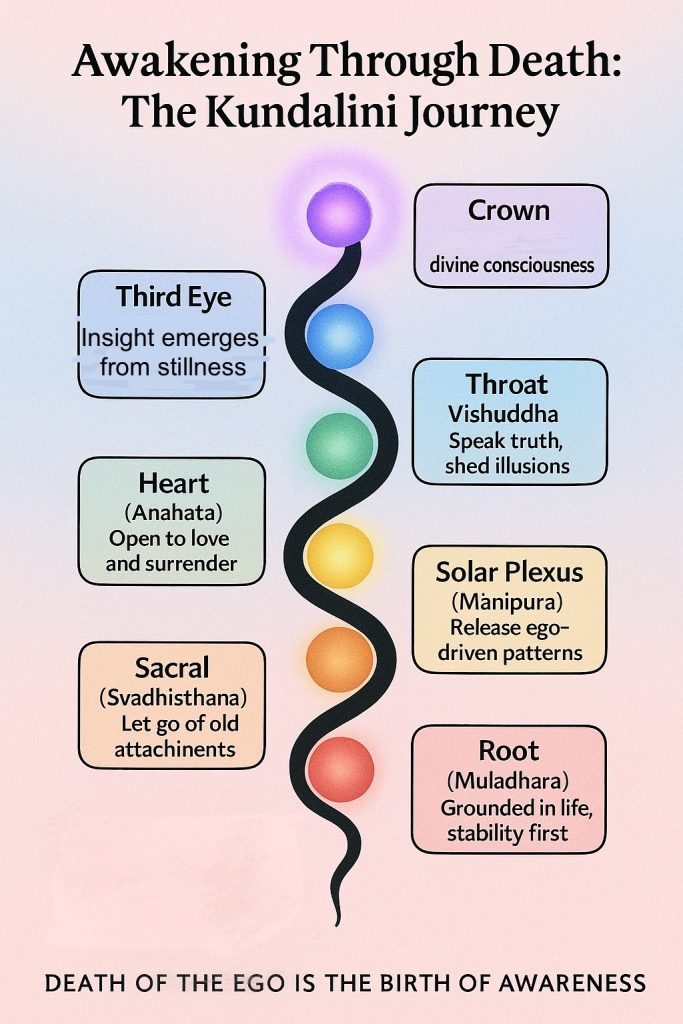

In Tantra, death is not feared but revered as a powerful transformative force. Rituals such as Mahāsamādhi (conscious exit) or śāva-samāveśa (self-realization in death) conceptualize the yogi’s death as a union with the divine. Tantra’s emphasis on kundalini awakening also involves symbolic death of ignorance: as the serpent power rises through the chakras, it shatters ego-bound identifications (often compared to shedding skins) and “kills” worldly attachments, culminating in a spiritual rebirth of awareness.

Many Tantric texts (e.g. Haṭha and Rājayoga treatises) thus describe advanced yogis as appearing “as if dead” while inwardly transcendent. The Haṭhapradīpikā, a classic 14th-century manual, states: “The yogi who is completely released from all states… remains as if dead… He is liberated. He is healthy, apparently sleeping while in the waking state, without inhalation and exhalation”. Such passages make explicit the Tantric view that ultimate freedom is like death to the ordinary world – a “death” that in turn procures immortality or absolute freedom.

Metaphorical Death: Ego Dissolution and Spiritual Awakening

Beyond scriptures, yoga teachers often speak of ego-death as a metaphor for transformation. Psychologically, “ego death” denotes the temporary loss of the sense of a separate self. In meditative or yogic experiences, practitioners may feel the personal ego dissolve, only to emerge with a wider perspective.

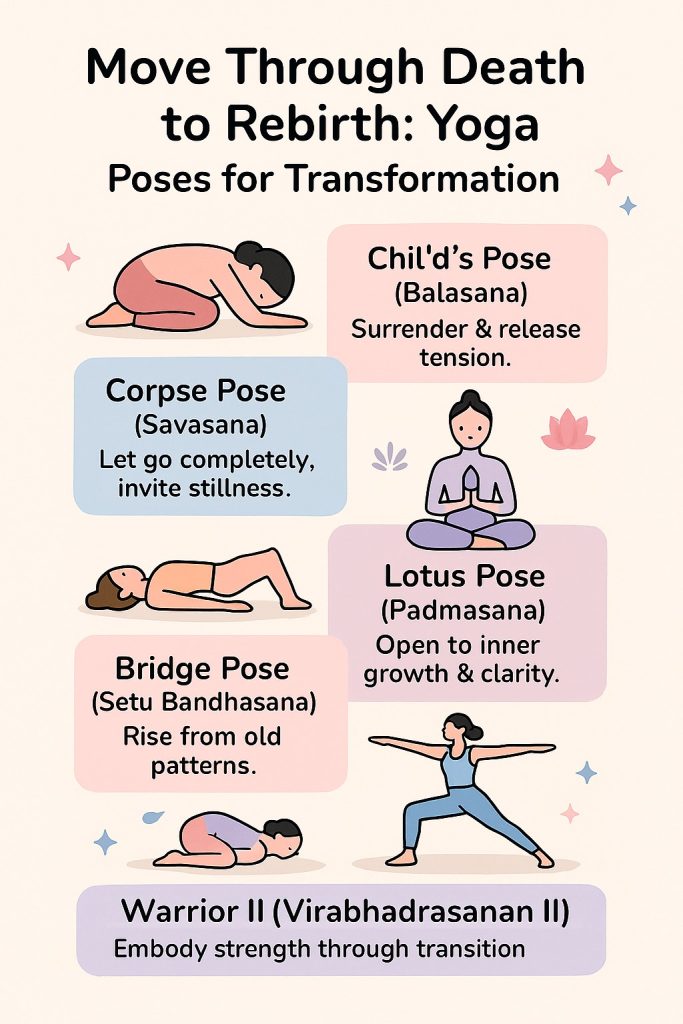

This is commonly phrased as “death of the ego” leading to rebirth of the soul or true Self. In fact, daily life provides many small “deaths” and rebirths: each night’s sleep and morning’s awakening can be seen as a mini death-rebirth cycle. As Mahatma Gandhi poetically put it, “Each night, when I go to sleep, I die. And the next morning, when I wake up, I am reborn”. Modern yogic teachers similarly emphasize this metaphor: lying in Savasana (corpse pose) at the end of practice is described as releasing the old self and “allowing the practitioner to die a little bit” and reconnect with the source of life.

Formally, the term “death” in yoga often signifies the final dissolution of egoic patterns. For example, Patanjali associates asmita (ego-sense) with mental impurities; its eradication is akin to a final end of personal identity. Contemporary psychology likewise notes that ego-loss has been a goal of many mystical traditions: “Ego death… as a practice can be traced to early shamanistic, mystical, and religious rites in which subjects sought ego death as a way of communion with the universe or with God”. After such experiences, people often report feeling “reborn” with renewed authenticity and clarity. In yoga, this is the inner rebirth of awareness – a shift from the small “I” to a universal consciousness.

Yogic Practices and Death Symbolism

Actual yoga practices reflect this symbolism. In aṣṭāṅga yoga, āsana and prāṇāyāma are sometimes viewed as “antidotes” to ordinary life that prepare one for spiritual rebirth. Eliade notes that the yogi “imposes… a petrified immobility of the body (āsana), the cadencing and suspension of respiration (prāṇāyāma)… [and] the immobility of thought” – all of which are the opposite of normal living processes. Holding the breath and stilling the mind are literally like simulating death within life.

Savasana (Corpse Pose) is the most obvious example: lying perfectly still invokes the image of a dead body, helping the practitioner “die” to muscular tension and everyday concerns. Yogic commentary insists that Savasana is far from trivial: it offers a glimpse of liberation. Georg Feuerstein writes that this pose “combines inner stillness with high energy, thus perfectly symbolizing the essence of yoga”. Practically, many Western teachers emphasize that in Savasana one “lets go of our worldly personas… and just connect with the source of life within”.

Other practices also carry death-rebirth symbolism. Prāṇāyāma techniques (especially kumbhaka, or breath retention) are traditionally considered to induce a state “as if dead”: a yogi in deep kumbhaka shows no breath or pulse for minutes. Classical texts encourage advanced students to master such “suspension of respiration,” equating it with mastery over life itself. Even the Shatkarmas (cleansing kriyas) can be interpreted metaphorically: some traditions say they “visualize the decomposition of the elements” in the body, as happens at death pdfcoffee.com, and thereby purify the psyche for rebirth.

In Tantra and Haṭha traditions, actual death yogas are described. For example, Mahāsamādhi is celebrated in stories of siddhas (realized masters) who consciously leave their bodies, often described as a final yoga success. Similarly, the Tibetan Yogas of the Bardo literally prepare one to meet death and attain a favorable rebirth or liberation. Tantric meditations may involve visualizing one’s own disintegration and regeneration (much like the Tibetan Book of the Dead’s visions), as Eliade notes a striking parallel between Tantric exercises and the bardo experience.

Contemporary Yoga: Tradition and Adaptation

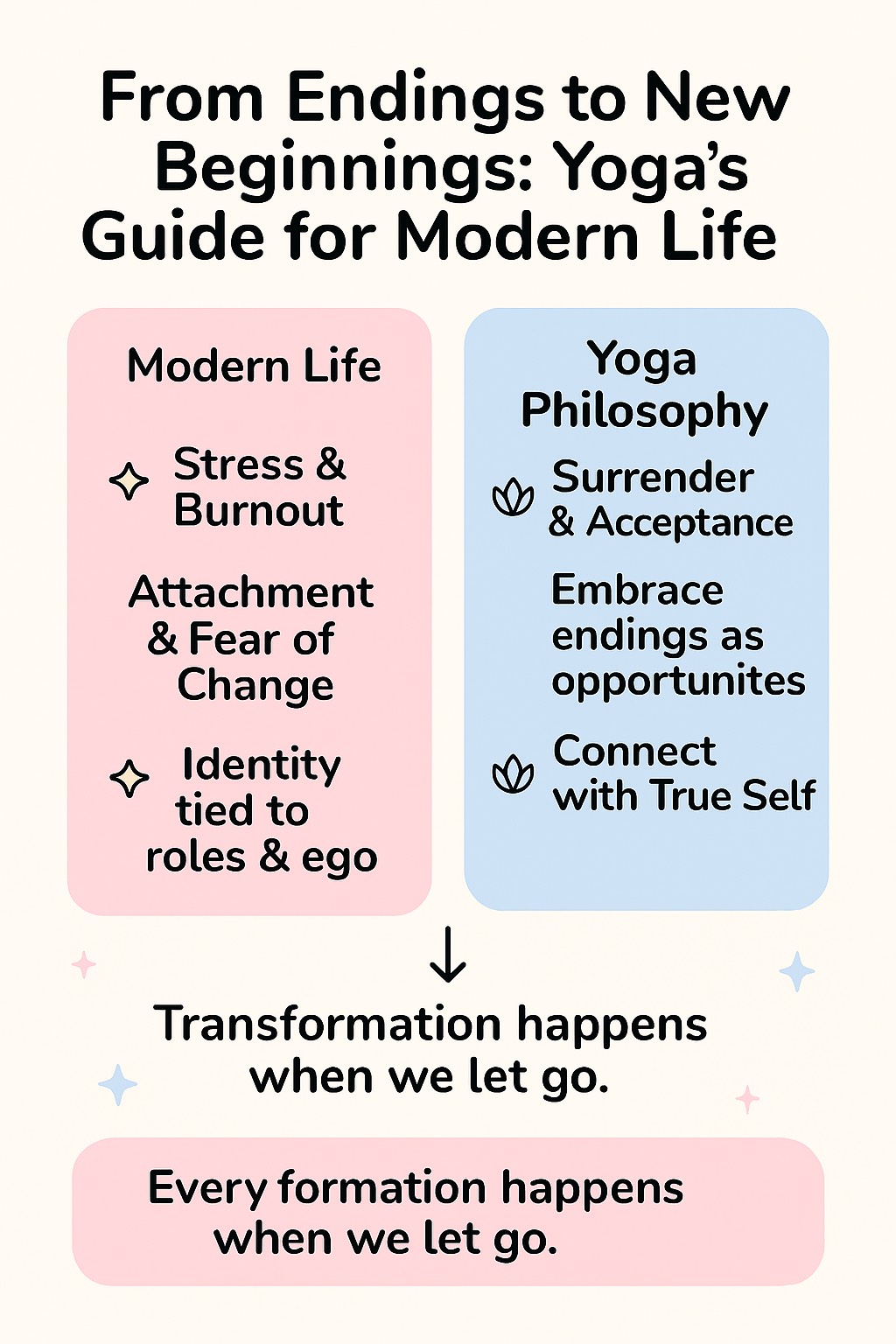

Modern yoga communities, while often focused on health, still echo these age-old symbols. Many teachers explicitly explain that end-of-class Savasana represents the death of the ego and the rebirth of spiritual awareness. Prāṇāyāma workshops sometimes highlight breath-holding as a “small death” practice that awakens inner power. Even simple metaphors like “yoga changes you from the inside out” evoke the death/rebirth theme.

However, Western yoga also adapts these ideas psychologically. The emphasis is often on personal transformation: for example, growing through crises or overcoming past conditioning. Teachers may speak of “shedding old habits” or “rebirthing your life” after intensive retreats. This reflects a secular version of the death–rebirth cycle: one sheds an outdated identity and emerges renewed. In group rituals or initiations (e.g. guru puja), novices may symbolically “die” to their former selves as they are welcomed into the lineage, echoing the initiatory rebirth of early sannyāsins.

Not all modern practitioners are conscious of these deep symbols, but many sense them intuitively. Science-based yoga (e.g. stress reduction) might speak of letting go or reaching mindfulness, but many spiritual teachers invoke the mystical language of death and rebirth. Even in yoga philosophy classes, the goal is framed as ending “rebirth cycles” – clearly connecting ancient metaphysics to personal growth.

Psychological and Spiritual Implications

The cycle of death and rebirth in yoga has profound implications for the individual’s inner life. Psychologically, “dying” to parts of oneself (old habits, fears, identities) is a metaphor for growth. By voluntarily “crucifying” the ego, one can free consciousness for new insight. This mirrors the jāti-mṛtyu-jīvanam (birth-death-rebirth) motif found in rites of passage anthropology: an ending (psychic death) followed by a new beginning. Buddhist and yogic texts alike teach that seeing the impermanence (anitya) of the ego-self is the doorway to awakening.

Many practitioners report an inner transformation consistent with this symbolism. For instance, after a deep meditation or kīrtanī (chanting), one may feel a “letting die” of personal worries, followed by an unexpected calm or bliss – effectively a microcosmic rebirth. Even facing actual death (through illness or loss) can be reframed in yogic terms as an opportunity for final liberation: philosophical traditions counsel meeting death with equanimity, having “withdrawn the senses into the self” in life. Thus yoga encourages practitioners to re-construe physical death not as terror but as the ultimate rebirth of the soul into freedom.

On a deeper level, the death–rebirth cycle symbolizes the dissolution of ignorance (avidyā). Every “death” in practice is a letting go of illusion, and every “rebirth” is a confirmation of one’s true nature. Psychologist and yogi Carl Jung might call this an archetypal transformation. In Eastern terms, it is the ongoing work of purification (saṃskāra-śuddhi) and realization. The goal is that, like a tree shedding dead leaves and sprouting anew, the practitioner gradually sheds karmic burdens and blossoms into a more awakened being.

In summary, across yogic literature and practice, death and rebirth are rich metaphors and cosmic realities. They represent ego death and spiritual awakening, the karmic cycle and final liberation, and the transformative journey every yogin undertakes. Whether described in the mystical verses of the Upaniṣads, the dialog of the Gītā, the sutras of Patañjali, or the teachings of modern yoga, the message is consistent: true Yoga transcends death, making the yoking of the individual self to the eternal possible.

Sources: Key scriptural references and scholarly analyses are cited above, including the Upaniṣads, Bhagavad Gītā, Patanjali’s Yoga Sūtras, and Tantric treatisesholy-bhagavad-gita.orgwisdomlib.orgwisdomlib.orgyogajournal.comen.wikipedia.org, as well as modern interpretationspdfcoffee.comyogajournal.combritannica.com. These illustrate how death–rebirth imagery functions both as a profound cosmic doctrine (karma, saṃsāra, mokṣa) and as a practical metaphor for personal transformation in yoga practice.